crying about when we tried to get croissants

(September 24, 2022)

flame is flame

(July 2, 2022)

thank you, Latvia, for being so kind

(May 19, 2022)

war diary pt.2

(March 19, 2022)

war diary pt.1

(March 4, 2022)

ДВРЗ/DWRF: The Darnitsya Wagon-Repair Factory

(October 22, 2021)

the Grey Heron Swamp

(May 1, 2020)

a spondyl clay brick for Oleksandr Osipov

(September 4, 2019)

updates from the Vidraniy neighborhood

(July 22nd, 2019)

the mulberry boys of the palace garden

(February 26th, 2019)

the wasp and the catterpillar, or how to work with the national city archives of Kyiv

(February 14th, 2019)

signals, plants, and labor camps

(January 1st, 2019)

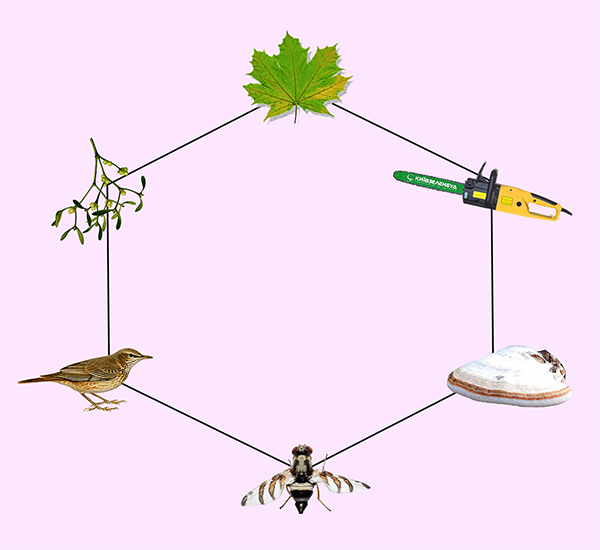

urban ecology chains are magic

(December 15, 2018)

crying about when we tried to get croissants

crying about when we tried to get croissants the second week of war

the joy of the bakery being open (though they didnt have anything)

then opened up to cry about something bigger and couldnt

the bigger is unthinkable

cant be mourned with tears

you can just cry around it

//

the talker will latch onto any available person

and it is the weakest of us who will cave to eventually respond

becoming vulnerable to the averaging effects of small talk

that would smooth us to group palatability

like water stone

//

keeping a journal to catch clues of the clench and meditate on same

e.g., get really serious about it; plan my whole life around it

not: “if it happens it happens”

not: to fall like snow till i curl up like a dog

//

selves as opposed to snowflakes can learn from experience

//

lisa how are you

dearest

we have

the most aromatic strawberries

cherries best in all the lands

but oh theyre crying

where is our lisa

oh oh

//

The National Security and Defense Council reports new signals in addition to the already existing air raid signal:

Signal for chemical danger—the sound of church bells.

Signal for radiation—the sound of the tocsin.

Signal for evacuation from the city—the sound of a train whistle.

//

all the time you spend worrying how much you get from me is time you could be spending giving me things

//

prefer to do nothing so as best to savor the sweet anticipation of infinite possibilities

//

probabilistic sweet spherical objects in the nighttime

//

inorganic material becomes homier

//

bringing small gifts and delights to my aging grandparents is exactly like how they would bring me gifts and delights when I was a small child, except when I bring them gifts, they say what is this shit

//

if you dont start replying to my letters i’m not going to release part 6 where draco and hermione trip and fall on top of each other while completing a special assignment in the forbidden forest

//

i suppose i’m going to go look for a river (massive sigh)

//

reviews of the shulyavske cemetery:

user ali baba

1 star

it is in wild desolation and not guarded, creepy! many drug addicts, leftover food, garbage, syringes, homeless people too, a lot

natasha pekar

5 stars

in summer and spring, there is beauty. in late may, acacia and lilac bloom. quietly, birds sing, squirrels jump, it’s like you’re in a forest. the nightingale sings early in the morning. but in the winter—flocks of crows. they whirl before the blizzard.

//

it turns out that where the children used to play, outside the shop “papyrus”, is also where their ancestors are buried

//

wartime updates from kyiv:

13 houses for bats were installed in Holosiivsky Park.

//

trees are flexing

shepherds are flexing

dogs are flexing

horses are flexing

deer are flexing

grasses are flexing

bushes are flexing

the basic model for flexing are the mountain peaks themselves

(ID)

//

he complained about not yet understanding where he was. it was necessary to understand in order to cultivate the melancholy of disconnection.

//

vazha says, theres no exit out of the Tbilisi botanical garden

that he watched his friends throats get slit open because they wanted to live in a free Ossetia, and still he hoisted a wounded man across his shoulders and hiked them out of there

(isnt it interesting how at some point you think life’s not like that)

vazha says that when two georgian men fight and a woman throws her hat on the ground, they must stop

(wish i had a hat like that)

vazha says, youre not georgian and anyways, that was before

(the world is in crisis)

vazha says its those liberal values and globalization, if we dont defend tradition, therell be nothing left to see for the tourists

(lol)

//

I want to pick a fight with every russian in the garden of cultivars but instead:

cupressus sempervirens

chimonanthus praecox

syringa vulgaris

pinus sabiniana

lonicera fragrantissima

juniperus chinensis

quercus iberica

//

funny you should be so bent on reconstitution when someone like you could be content to be dead for a while

flame is flame

my last ditch effort for semiotic exchange with my mother was a card

7 year old

indexical chain

leading through frame,

mirror,

behind the drawn flame

she never made it

i could never touch her

scare her out of the tree

the void was so obviously me

that i never even truly desired

a thing or a way

only wanted the state of wanting

this being the thinnest of threads

the most easy to sever

and now with the war

making a hole big enough

for half a country to fall inside

its what I feel calmest touching

in those moments when I almost know

form is form

emptiness is emptiness

and the sunniest

are the scariest days

//

i used to talk to horses, now they fly by like lanterns

thank you, Latvia, for being so kind

and thank you to Nuar Alsadir who showed me I can just give you this.

//

roads like small veins capitals like small stones

red-backed train blinding me en route to daugavpils

where they’re mad about foreign flags and the price of kebabs

at summer solstice

found a sandy hill to train myself in

staying with my melancholy

at the end of gallows street

suicides buried to my right

witches beneath me

two gothic water towers behind

youd think theres too much sun, sand, and ants, but winters only been gone two days and they almost lost it at the park ripping their clothes off and

im a work of a lifetime, a grand disappointment

the towers meanwhile were meant to form an isosceles triangle but the city ran out of money

//

* this tear means that I want to come back and that I will come back as soon as I can and that I would like you to want this too.

is the giant agave still alive in the garden of Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky?

if it is not alive

are the blind dolphins still alive off the coast of Olbia?

if they are not alive

I know a couple more places

//

In Latvia the trees are their own monkey-wrench gang. They’re full of bullets, and when they’re laid down into the cutting machines, they break them all on their own.

//

vigorously chews her salad like a herbivore during the cambrian explosion

//

march 25, 2022

the room in which we stay has thin walls. my cat is often in the throes of fear. all night, she scratches at the door. on the other side of the door is where danger lies, but she finds sitting in the room unbearable too. now she has bunched herself up between the fitted sheet and mattress, forming a smooth mound, like a kurgan, which for her certainly could be either fortress or grave depending on how she chooses to look at it.

at times the kurgan becomes agitated and bores its way around the mattress like a mole. the fur and cloth rub, sparking static. any further move makes the situation worse. in chess, this condition is called zugzwang. some weeks ago, a journalist used that word to describe putin’s options. this singular usage does not do the word justice, I feel. I believe this word is so widely applicable that it should become an interjection.

//

hide the cat

move the cat

breathe deeper

an entire jar of thuja oil has spilled karmic blessings on the floor

//

On the origins of a craft beer collaboration

M: We have, for example, Titurga…

I: …Ledurga.

M: Ledurga.

L: These are all names of rivers?

I: Small towns.

M: But towns come from rivers. Like Ventspils is on the Venta and Daugavpils is in the Daugava.

L: You guys have a lot of rivers here.

M: Well not a lot.

L: A lot of water.

I: There’s quite a few rivers.

M: Not huge ones.

L: Ones that feed into bogs.

M: And this name, Urga, it’s a Livonian name. Livonians were the first settlers here. They are not Indo-European, they are in the Finno-Ugric language group. Which is also the Finnish language and Hungarian, Estonian. Nurme is actually a Livonian name.

I: What does it mean?

M: Pl’ava. Meadow.

L: So this (Upurga) is the name of something in that language…

M: Upurga could mean… I don’t know a place like that.

I: Since Upe is river and Urga is little spring, maybe it’s a River Spring.

M: In Latvian Upe is river… You know I’ve never asked them. I should ask them. Maybe it’s a connection of two languages together. Upe means river and Urga means river.

L: …A name that’s less about the thing it is talking about and more about the connection of two languages.

A river flows between two places.

//

youth

that hysterical laugh

about something to do with the holocaust

and an open khaki puffer despite the frost

shows a white neck straining tendons

covering up a wide-open mouth with a coy hand

to greet his grey corduroy red braces and hair

youre so skinny and im so beautiful

im worthy

im worthy

walking down the street

hoping i meet

all the people im avoiding

//

when there are so few people on the street every conversation becomes an event

//

Alisa says people don’t understand the full scope of the issue, which is why they haven’t packed 72-hour bags.

//

april 10, 2022

for Ilya

you don’t need to look for a house in the countryside far away from well-wishers and your best friends when you’re in the Baltics. I realize now that the surprise expressed by Rigans at the ten-cycle-four-season daily weather was feigned to humor me. “I do not wish to use social media / to produce anything / to live in the city / to see anyone / ever / or to speak / or to commune with structures of any rigidity or size” is not a necessary slope to slip to the bottom of when you’re soaked through with saltwater the color of a root beer float or rainwater delivered in its consistency. everybody understands these things; climatic conditions are proprietary excuses sewn into the lining of these madly scurrying clouds, into the inner wingseams of these madly yelling seagulls, who go to such great lengths so that you don’t have to. before you take this mossy hollow for vocation however consider eight months of winter, consider yesterday’s snow, or that the growing season has not yet begun. nobody is in a rush to sow and those who were are now regretful. eagerness is blight. is this heaven? of a sort.

War Diary pt. 2

mar 10

westwardly rolling through dim-dark countryside, narrowly missed a bomb dropping in Berdychyv, feeling close to nothing. same for the lady next to me, I think. she is popping bubbles on her phone. the moon is waxing.

7am

snow covered hills smoothly slide past, peach blue sky gently backlights their peaks, and my chest contracts every ten seconds to meet that broad sour sting, the elephant foot, the diesel comixture, already familiar to those who’ve decided ptsd is to play another season.

worldwide sit-in? should I just yell on any street I'm on? self-incinerate? how do I make people who can, do something? how can we stop the latest Ukrainian genocide? how do we stop bombs on babies? stop nuclear terrorism?

we keep forgetting about it all intermittently: the controller yells at the lady. the boy cries over his plastic car.

2pm

the dawning realization

that i am in a new country

i have left my home

and i dont know where i am going

mar 11

I’m crying on the way to meet K. on Oktagon Square because the dust-covered blue Lanos has a sheet of paper saying ДЕТИ (CHILDREN) on its windshield and someone in small pink pajamas is eating a banana in the front seat and I can see now that these will be our distinguishing signs as we scatter westwards: a dust-covered Lanos, a sign begging you not to shoot our children.

mar 12

tourniquets, derealization

mar 13

P. believes I am concussed. For exactly two weeks my neurons went down the road less traveled. Again, it isn’t about the taken road, it’s about the absence from the other road, the slippage.

mar 14

speaking

W. says Rudy didn’t know hands when she got him. Forks, cups, plates… Those Hungarian dogs who do know these things are confused about what to do with them. This is because Hungarians call their dogs after food. Blueberry, Muesli, Dinner Roll… When dogs share names with consumables, they may have a hard time understanding their place among them; they may find hidden affinities towards utensils; they might see, after the croissant crumbs are gone and the licked plate on the floor lingers, an overture in ceramics. Rudy’s plates are aloof. This brings Rudy’s sense of the kitchen closer to my own and may be seen as an advantage. But when W. leaves, he won’t be taken in by my hands, no thing speaks to him, and there’s nothing to do but lie by the door and listen to the elevator move up and down.

moving

W. moved here because of a burly Hungarian man who did not speak and did not know how to live. She spent her life savings buying them an apartment, and then she spent months trying to get the right documents done, and now she’ll spend months getting them undone, so that she and Rudy can get in the camper van and go somewhere far away from putin. (Rudy hates the burly Hungarian man, by the way, though all other dogs love him.) K. is moving too. Madrid, then Lisbon. No use staying where so much of her life and her business is tied up with Russians. N. is moving back, from Dahab to Riga, to Warsaw, to Ivano-Frankivsk. She doesn’t know what she’ll do there, but Dahab is an unbearable vacuum. T. is moving from Poland to Germany. I. is moving to Batumi, or maybe to Paris. C. is moving from Warsaw to Lviv and back again continuously. D. can’t move anywhere because of the mortgage. P. can’t move anywhere because of the mobilization. E. can’t move anywhere because he is in a basement and does not hear or hears but does not understand that today the sirens mean evacuation. F. no longer uses speech for communication, his plans are unclear.

I am traveling to Riga on Thursday. I wonder what they call their dogs there.

mar 17

V. has lip fillers, flashy clothes, her tone is demanding. I hadn’t realized that I assumed she was Russian until I found myself surprised that she was Ukrainian. I refrain from generalization after pilots bomb the theater in Mariupol, which was flanked by two giant signs you can read from the air spelling “CHILDREN”. I refrain from generalization after I learn that 71% of Russians are “proud” of the war. And, in my more affectless moments, I do not think that “all Russians” are responsible. Or rather, they are. But so are you for Yemen. So are you for Syria. And still I won’t spit in your face. I won’t spit in my own face. Yet something about the lip fillers… If love won’t overcome war, maybe internalized intersectional misogyny will… be some sort of bad humor for bad days.

V. is from Kharkiv and “works in the social sphere” by which she means she directs large-scale projects for several culture-focused NGOs. She left her husband back home — a surgeon working on the frontlines, delivering babies in bomb shelters, putting people’s intestines back where they belong, sorting humanitarian aid, occasionally escorting unaccompanied dogs to the train station. She’s delivering her teenage daughter and her mother (“who is herself like a child”) to family in Georgia. Then she’ll return, if birds don’t get in her way. Yesterday her flight to Tbilisi was canceled when two birds flew into the plane's engine simultaneously.

V. says the war has made her rediscover her purpose as a woman. V. ran the largest documentary film festival in Kharkiv. And now Der Spiegel wants her to run around Kharkiv with a Go Pro. As we can all well understand, this is a waste. A woman must… (V. weaves her fingers into a lock, a net) …a woman must help her man do what he does. At the very least, a woman must be home when he arrives, shell-shocked, and help him laugh about how his salary is still only $800 a month. And about how today’s humanitarian convoy delivered hundreds of useless ladies’ nightgowns with decorative netting.

A pair of Russian fighters was flying near Kalanchak. The first raised a flock of geese who decided to fulfill their patriotic duty to the people of Ukraine. According to SpecMachinery.com.ua, one or more birds heroically fell into the engine of a Russian fighter, as a result of which it fell into the swamp.

War Diary pt. 1

jan 24

It’s becoming harder to communicate “out” of the middle. Especially, it seems, facing the blizzard’s drift. Fat flakes clump to eyeballs that see little, anyhow — maybe a thin pearlescent ribbon in sewage-water fog, maybe scum-green flats of n-gon ice doing slow twists down the Dnipro. Frozen fingers don’t type.

What would I say? I am afraid! I am not afraid. It’s alright! It’s not alright. I will conceptualize this moment in writing! Like it’s necessary, like it hasn’t been done before.

Things may happen in moments, but some catastrophes are the natural appendages of a mounting anxiety. Pools at the end of a meandering waterslide, a promise.

For the first 15 years of my life, I craved it, willed the fabric to rip. Drew graves, spoke with thunder. Ardent weaver moonlighting mutiny. For the next 15 years of my life, I still willed it, less ardently. It became apparent that I could easily kill myself, for example, and that I did not yet want to.

feb 12

Recently I just haven’t been able to be still. I want to rove like a roomba. Directly in the flow is when it’s best to write, though it’s harder and your fingers freeze right off. Now my brain has been wiped clean by hormetic stress. I prefer it to hermetic stress. It might seem like you’re full of bits of thread and electric shocks, like you’ll burst if you stay still a second longer. But it doesn’t have to be that way. All you have to do is put your work device in a bag and set out into the city. Walk through your neighborhood and purchase a hat, purchase a sourdough pie with sauerkraut, gaze wistfully at chocolate potatoes, at nougat parallelepipeds lit up in a glass vitrine, thinking all the while about how all this might be blown to smithereens next week or the week after — not likely but not impossible — glazed ruby cocoa-covered hazelnuts exploding ecstatically every which way, and then realize that compared to the ruby cocoa-covered hazelnuts, you don’t actually give a flying fuck, you’re full of random energetic impulses but you seem to have lost the ability to emotionally respond, ecstatically or otherwise. And anyways, maybe if you left the house sooner, there wouldn’t even be any impulses.

He says, “I am in the middle of a frozen bog with stunted pines and I have not heard from you in 5 hours, do you no longer love me? Have you unloved me?” Which one of us is the seducer?

I think I am communicating regularly, but it’s really a shot in the dark. I believe that what exits my mouth is a decodable message, not suspect, something appropriate to the conversation, but I cannot be completely sure. Pretending like I feel something about anything was kind of fun but is getting a bit boring.

feb 15

O. will arrive any minute. She was not going to come until the end of the month, but we may get invaded tomorrow, and I might disappear with the money. She’d ask for next month’s too if she could but she can’t.

K. says she is not going to give Putin any gratification. She is not altering her life in any way, besides the fact that she is leaving to the Venice Biennale and won’t return for a month. I hope she gets to leave. I thought for a moment that I was annoyed at this, or sardonic about this, or sneering at this, but I am not, because we shared a bed and secrets and it became less clear where one of us begins and the other ends.

feb 16

How I am preparing for war:

I have abandoned my plan to pack an emergency bag.

I am traveling to Bereznyaki to buy four Soviet-era glass salad bowls.

A: I’ve got a similar situation.

L: I am too fatigued for self-preservation.

A: Same here. Today I am in pajamas, exclusively.

L: If we are taken hostage, I really hope there’ll be something fun or tasty there. Truth or dare, tag, pastries. (My present level of consciousness makes me think my brain has been assaulted by some chemical. But no, just information. I think about this for a moment, then forget what I was thinking about and back to pastries.)

A: Exactly. I can’t concentrate at all. Time is viscous, I’m exhausted, I forget about all my actions halfway, then suddenly recall them. Some kind of situational dementia.

L: Same same same.

The curse has far to go before it runs itself out and the curse is time.

Head stuffed with wool and neck with a crick, darting unseeingly between feeds that don’t even feed anymore.

I do not sense myself.

I am anxiously binging every way I can.

Zelensky doesnt see troops withdrawn from the border.

Biden doesnt see troops withdrawn from the border.

My Russian friend says, “I was so relieved today to hear Biden is canceling the war. It occurred to me that I have been worried. I just realized what people in Ukraine must feel.”

I am both exhausted and nervously energetic.

I say, “Figuratively. You mean canceling figuratively, right? As a joke, right?”

He says, “It is very useful to receive screenshots from Ukrainians discussing the situation. There is a tendency here to place equal blame on Biden and Putin, because it is psychologically comfortable. This inner picture is easy but incorrect. It is a psychic solidarity that breeds deformations, adaptations. Adaptations are life-sustaining.”

I am so tired and burned out. I want to sigh with relief and break out of this whirlpool. But this isn’t possible, though the day has somehow passed and it was the day towards which everything was clotting. But nothing changed.

He says, “I feel that you are living through something bad, something inaccessible to me.”

Everything is unacceptable. It is worthy of rage. What it does to us.

feb 17

a kindergarten was bombed in Lugansk and now somebody must carry the blame. they’re burning papers and something else that makes black smoke at the Russian embassy.

on Sunday I am having six guests, and I’ll suggest we use my oracle cards to divine on any question of their choosing. this should be good; the NYT says card reading is on the rise because of the uncertain times we live in. I dont actually know if dinner will happen because we might get invaded before Sunday, but I’m preparing as if it is.

mechanical things are fine. I am working and going to the gym. the more delicate and complex layers are nonexistent. I am not thinking or feeling or creating anything. I am not in that sort of mood. I am in the mood to survive.

Russia is escalating. Russia has expelled an ambassador. Russia has installed a pontoon bridge in Pripyat. Russia is moving towards an imminent invasion.

I would like a cherry bun.

feb 18

Meditate and do some banal breathing exercises and time flows slower. Not viscous time, stretchy time. You can stuff more things in it.

feb 19

How the war will save me with breakthrough pain:

I have not slept but I am meeting with V. to explore Zhukov Island, something I’ve been meaning to do for years. Not with V., never with V., but maybe it’s wartime, and I am experiencing sudden impulses to come closer.

I am running low on money but I am buying sparkling wine on sale and stringing doilies into a garland. Tomorrow six people are coming over for a potluck dinner. I don’t care how I’ll look or how I’ll sound. I want to light candles.

I haven’t been able to since June, but now I’m reading cards again. I asked L. if she’d want to. Though she scares me a little. But that’s precisely why I want to start with her. As if the discomfort, some gap between us, is exactly what makes me feel more human. Pontoon bridges not only for Pripyat’.

Grandmother says occupation wasn’t so bad. She was in Kharkiv and her mother washed dishes in a hospital. The Germans lived behind a curtain.

///

How to heal yourself of wartime anxiety:

Meet with V. to go to the water pumping station and Vodnikov Island, but never actually reach either. Instead: Walk through old oaks in a steppe savanna, across the occasional thawing lake, and talk about pigeons, fathers, guinea pig dolphins, scoliosis, keeping goats, catching siskins, types of memory, the freedom of maritime professions, walking westward, vampires, 16mm film, the polonyna, stalin’s metro, trains, and anything else you can think of. And yes, even war.

feb 20

1 AM

A.: Will he attack or won’t he?

I let every guest around the table cut the deck in turn. Pull the top card. It’s “Chernozem”. The one Ukrainian tribute card in the deck.

An equivocal message. Rich land. Great starting advantages. Privilege. Prize.

Will he or won’t he?

feb 21

K. bought a butterfly.

K: When she came out of her cocoon, something I wanted to say to myself emerged and hit me square on the forehead. Her wing is crushed, she drifts this way and that. No magnet in her head. I sat for two days over her. She was meant to be a sex machine, exclusively for my pleasure. She became a mandala. Like an injured child. And a new reality grew out of that new center.

K. forms her fingers into something like a branched sphere.

Are we in a collective delirium?

K: That double rainbow.

L: That split-second mushroom cloud spliced into a video about laser epilation.

feb 22

Somehow I walked all the way to my grandparents’ house while reading the news. There are some people, I hear, who manage not to do it. But it always turns out that they live with or are close with someone who reads. When I lifted my eyes I thought I could see unity in others’ faces. Towards the evening, I just thought everyone looked tired.

feb 23

I have lost access to some components of myself. I. said this often happens to him when he is ill or tired. I. says a joint snapped and my fantasy body went away and a solid body appeared instead. I said there may be a loss of innocence but I often feel helpless and scared like a child. Later, I. said (only a period separates us apparently) that he feared something solid and transparent arose between us. I said, it’s only wax. I was thinking of what to remelt the dinner candle into. I. must be afraid of solid things, but I think he craves them too.

Plants are good meditational objects. There are two things touching: a lavender woolen string and the gray fur of a pussy willow catkin. The lavender string hangs down from a garland of doilies, emergency decorations from Sunday’s anxiety dinner. The pussy willow branches were lying under their bushes in the sand when I went to clear my head on Truhanov Island, so I didn’t even need to use my knife to pick them. Pussy willows are only called that during the spring. At other times of the year, they are regular willows. There is also the possibility for an instantaneous transformation: user Sima says that any ива (willow) that is brought to church on Вербное воскресенье (Pussy Willow Sunday, Palm Sunday), automatically becomes a pussy willow (верба). Gleaning residues of religion’s microeconomics is gleaning’s outpost. The Torah and the Bible say grapes, olives, dropped things, are all for the poor and for strangers. In 1933—the height of Stalin’s starvation genocide of Ukrainians—the Law of Spikelets said 159,973 gleaners should receive 10-year sentences.

It’s hard to write anything after this but there’s one more thing about gleaning.

To woolgather is to daydream. When you are gleaning from a moving body that perambulates, you begin to wander yourself. I. says that when I describe things to him, he sees them as though they are made of colored wool. They are actually constructed of pixels, fragments of still and moving images I send him over Telegram. I wonder if he is dreaming.

feb 25

yesterday i woke up as if a sphere of light entered my body and into my veins

it was as if suddenly the world was alive and it was after me. the air was thick and hot and palpable.

everything that happened in the next 15 hours happened impossibly quickly and slowly. my left thumb is bruising internally from typing. in the metro, people ran every which way with bags. only one woman sat on a bench in the middle of the platform with her two cats in a see-through backpack.

should we play monopoly?

now I am in the basement with the family from #13. the basement was built by german POWs. the family is kind and offer me coffee and chocolate and blankets.

at least our shrimp will defrost

what?

didnt you decide to defrost something?

shrimp, but I put them in the fridge. at least i didn't put the water on to boil.

now they've put me on the big green satin chair with the gold leaf design. i will preside over this moment, not simply sit.

feb 27

oh no, time warp, I will have to reconstitute later.

…

I believe we are all about to die and I can’t tell any of my friends because it’s not good for morale.

//

Fortune-telling for L.

L. writes me:

When I was a child I had a vision and a prophecy that I will die at 36.

I have a couple days left till I’m 37; I just had severe Corona; I see repeating numbers everywhere, absolutely everywhere; three months ago I met a person whom I considered a guide to some degree. It was important to me that you and I meet to read cards.

During my last walk to the woods I said goodbye to everything, cut ties, gave my thanks, let go.

There are 2 days left till I am 37 and I am finding this death drive so exhausting.

//

I write:

The top card concerns what awaits you. The bottom card is complementary. I am reading this as a promise of freedom. I do not see death at all. Longevity, health, power, cleanliness, serenity, diversity. Some kind of transition to a coil of complete maturity is possible. I read the bottom card as regarding the prophecy. The prophecy appeared as a "unit of necessary elemental independence", intertwined with you during the "first trials". It fulfilled certain desires, which was valuable.

It seems to me that what will die is the need for this prophecy. This is not an annihilating explosion, but a new loop. Maybe it’s not very attractive, a bit boring. How could it compare with the death drive.

For some reason I want to say sorry :]

//

here’s something parents do in Ukraine when they want their children to eat: they bring up a spoonful of something to the child’s mouth and say “for mommy”. then they bring up another spoonful, “for daddy”. then for grandma and grandpa. for the dog. however many spoonfuls. my grandfather would reidentify the plate: mashed potatoes are sand. slices of beef tongue — flat rocks on the shore. garlic pickle — palm tree. all flying into my mouth at terrible speeds on a silver-steel jet plane.

beyond force feeding, it occurs to me now, this is another transgression: a sacrament. a metonymical transfer. here’s a thing about lack of boundaries: it prepares you for death.

perhaps this is why I am visited by spells of calm regarding the increasing possibility (“Putin orders nuclear deterrence”) that I will soon die. when your body has never quite been yours, it is easier to recognize that sure, I’ll be gone, but I am not very different from the people who left or were never here. and some of those people share my thoughts and ideas. things that are important to me will continue. also, the tragedy of my body, my life, dissolves in the collective tragedy of our bodies, our lives. I listen to the thoughts of my friends, around town, around the country, and I think it would be an honor to die together.

feb 28

found myself in the apartment with the telescope

ate porridge, oil painting of the couple hugging

now we are going to the store and to give blood

guard from konotop stuck in a laura ashley store

45% off unique mongolian cashmere

money falls out of pocket — “ah, thats historical”

woke up this morning with the sense that we are going to get nuked

V. keeps running around and talking on the phone and L. keeps begging him to stay still in the basement

i can understand wool now

wool instead of brains

i used to think it was offensive

how fast do rockets fly? if we get a call from bucha (where they have no water, no food, but they have phones) telling us 20 rockets just flew past heading towards us, is it of any practical use?

shows us how to make “hedgehogs”, birds singing in the background

I am beginning to grow tired, a longterm kind of weariness that is aching in my eyes and nose and back and joints. It isnt just from sleeping in strange places or sitting all day. It is from the news and from my neighbors, with whom I spend hours every day.

mar 2

wow I think ive had refugee syndrome at least since I was 15

mar 4

we don’t take showers because it doesn’t seem important

sharpest sensations of the past 12 hours:

- Russians attacked the Zaporizhia nuclear power plant, ten times the size of Chernobyl; (NATO says it will not get involved) (where my together-life cthulucene OOO rhizomatic community-oriented decolonial climate crisis scholars at, why so silent)

- rooibos kombucha had a strange after-taste

P. and I found a giant head of Circassian cheese at the “Milk from the Farmer” store

V.’s parents have no electricity or gas and can’t leave their basement

people are drinking rainwater from drainage pipes in Mariupol

K. and S. are panicking and want to run to our house in the dark

P. and I laughed at jokes and barely acknowledged background gunfire and explosions while we took a walk in the park

I have not been sheltering during sirens for 3 days now

I realized I won’t leave P., or K., or S., or grandparents, or P.’s parents behind either way so I might as well pretend none of this exists

L. is still alive, by the way

mar 5

we are standing next to a canister of flaming tree branches billowing grey beards of smoke across the four-way by the C— Mall… sandbags, cement blocks, giant hedgehogs, the many men of TrO with yellow bands and rifles… these are the backdrop to P.’s mom struggling to tell us, over the noise, that she and the director of the Institute are on top of everything. they’ve just had a lovely talk and they’ve got strategies for reopening, they’ve got strategies for the annual startup festival, build it and they will come. this is not a thing, because every half an hour we hear explosions, and people just outside of kyiv have no food, and their houses are burning, and evacuees are shot on their way to safety, people are shot on the doorsteps of their homes, not one hour from here, and people are leaving this place and nobody is returning.

I wouldn’t say we are doing well. it’s been 10 days and I have taken 2 showers, scrolled news 10 days when I said I wouldn’t, worked no days when I said I would, get high every night, and primarily engage with the world by means of a continuous relationship with dried fruit. I no longer take precautionary measures; the people in the subway have begun to smell, basements cave, bunkers are unfit for life.

met E.B. on Lvivska Square, twinkle in her eye. she said she’s been having a ball with it. let’s publish a new issue of Noga! let’s have a candle-lit dinner! she’s been writing articles we can’t read, they’re in German, but there are a lot of them.

Podil is empty compared to the working-class neighborhood I now stay in, though someone did shoot something right next to us just as we came down the hill. S. and K. trekked here in a panic yesterday, too many things flying past at their old place, and the area completely deserted. K. says it’s much calmer in the center, but the only things for sale at the supermarket are oysters and ground cherries.

Here are some things i could fit into two hiking backpacks:

socks

underwear

lamp

Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora’s Daughters and Botany in England 1760 to 1860 by Ann B. Shteir

Botany, sexuality & women’s writing 1760-1830: From Modest Shoot to Forward Plant by Sam George

toothbrush charger

10 kiwis

sugar-free pomegranate sauce

a tub of Turkish yogurt

1 cabbage

4 tomatoes

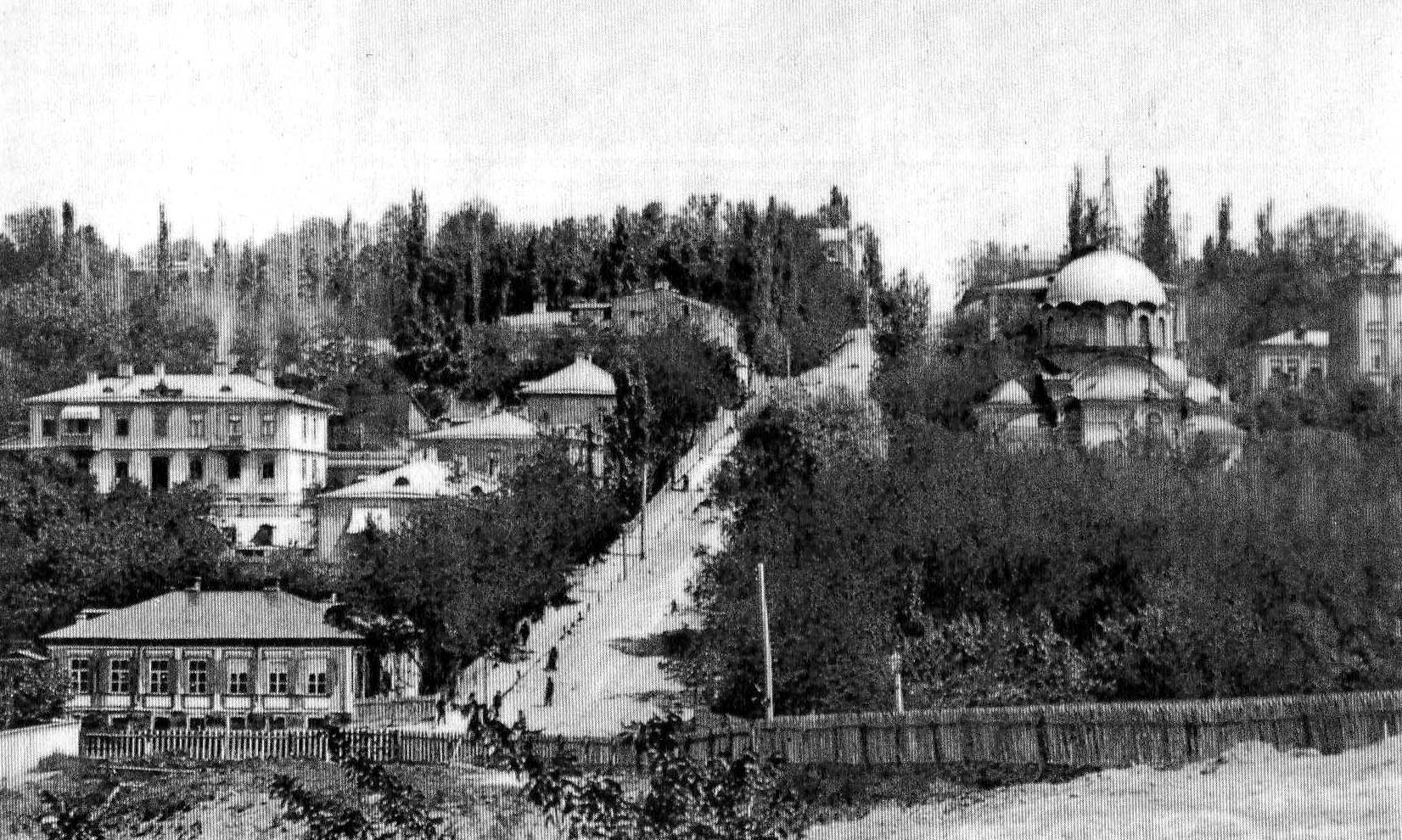

ДВРЗ/DWRF: The Darnitsya Wagon-Repair Factory

On a Tour of DWRF

The straight-traveled road is filled with fallen wood,

The road is filled and is overgrown with grass,

Along that straight-traveled road

No one has passed on foot,

No one has ridden past on a good steed.

By that Swamp, by that Black Swamp,

By that birch, by that crooked birch,

By that stream, by Smorodina,

By that cross, by that cross of Lebanon

Sits Nightingale the Robber in a damp oak,

Sits Nightingale the Robber, Odikhmanty's son.

[Source: A. F. Gilferding, Onega Bylinas]

At first he was just a man, grey-haired and slight, who appeared seemingly out of nowhere and insisted on going first, though he clearly wasn't a fast walker. I thought he was trying to teach us how to truly enjoy the outdoors. Well, I thought, I can, and I touched the wet lichen on the pine and I pointed at the yarrow and whispered, yarrow!

Our tour group met close to the river fork, where the northern and southern arms of the Darnitsya river split, just inside the Brovary pine forest. Not far from here, I had seen birches lie down as if pushed about by a giant hand.

A tornado did it, says one man. 10 meters across. A band passed, “vzzhhhhuh,” and straight fell them all.

Our guide says that here, at the river fork, the legendary Nightingale the Robber had operated.

Nightingale whistles like a nightingale,

He screams, the villain robber, like a wild animal,

And from the whistle of a nightingale,

And from the scream of a wild animal

All the grasses and meadows become entangled,

All the azure flowers lose their petals,

All the dark woods bend down to the earth,

And all the people there lie dead.

The older man was with a younger woman. They both wore rain ponchos. She walked behind him, and they would on occasion point things out to one another, and to everybody generally. They looked more satisfied than we did and nodded with confidence at the ferns, the wet mounds of clay, the rope swing by the lake. With time, it became clear that the man had seen these pines when he was young, when the pines were young, and watched the locals put up fences around their houses using old, green, wooden boards they removed from train wagons. The people had started to steal them. In the center of town, just outside the forest, there was a satirical board on which a resident caricaturist softly shamed wagon-repair workers who drank too much or were involved in petty crimes. Regarding the old train wagon boards, it was promptly decreed they could be bought or distributed (the satirical board only had so much space).

///

A Brief Historical Interlude

The pines meanwhile had been planted by Stalin, not personally, during a greening effort in the 50s, after a razing effort in the 30s. And, during that same time, there was another green-board fence, not too far off, behind the pines, known as The Green Fence, where, after another razing effort, Stalin planted whoever was undesirable, some 50,000 to 100,000 people in the ground, we do not know for sure. These are such things as the weather, as nitrogen cycles, as the wind. Could you calculate where the wind blows each second? No. So it is with bodies. They slip through the cracks. Some confuse and confound.

Today it’s 38 years since the death of M. Khvylovy. I decided to spend this day here, alone, among the blooming trees and the birds. To hear only their truthful language. Not long ago, in Darnitsya, by the graves in the forest where the fascists shot thousands of our prisoners, some shepherds found another grave with hundreds of bodies. The newspaper printed a notice about yet another evil committed by the occupying army. Meanwhile, the forensic team established that the bodies are from… 1937! Nobody had known about them till now. So, whose prisoners were they?

[source: Oles Honchar. May 13, 1971]

///

Back to the Tour of DWRF

At break times, as a young boy, the man swam in this lake naked because it was a school day and nobody had spare clothes. It had been called Bull Swamp. This is either because the bulls pulled someone out of the swamp, or because the bulls had to be pulled out of the swamp—the nuances of the situation have been lost. When the wagon-repair workers began to live here, they drained the swamp, expanded it, and the swamp became a lake called “Little Birch”. Summer camp was right here too. It was called "Little Pine”.

The whole railroad was up in that camp. This whole town is vedomstvenniy [industry-sponsored, distributed to workers based on merit]. Cut off from the whole world. It is rare for a DWRFer to leave this silence. You can walk down the road and not see a single car.

Did your whole family work at the wagon-repair factory?

Of course, everyone's did. The factory still works. Used to work in four shifts. Now it works half of one. The only one still in operation. We’ve got a museum. And over there they’d find bombs and detonate them. Day and night the whistle of breaks.

I don't know when the change began, but by the time we had seen the dilapidated pre-war luxury apartments, of which only a titanic carcass, with eye holes gaping into the sky, was left; and seen the packs of homeless dogs, which scared us, but were either ignored or deftly deflected by local children with a twisting swish of a stick; and seen the Darnitsky Wagon-Repair Factory itself; and seen the pedestal, out front, where Lenin once stood (they only put him near important enterprises); by the time we had seen all this, the man had grown sour, surly, and quarrelsome.

The tram, he was sure, never went as far as was implied.

This was a pre-war tram, though!

Still.

By the water tower, the angle at which it was indicated another water tower was located threw him into a rage. He and the guide engaged in a disjointed debate, drawing closer, closer, then suddenly splitting apart like magnets. Their words to one another flew out from behind corners, darted between spurred, jerky silences; nobody could tell whether a conversation was really going on. The sounds of the man’s grumbles and shouts were carried every which way by the wind. The group had spread out and was moving on to something better. The guide walked quickly ahead, leading the way, and some of those left in close proximity to the man chuckled good-naturedly.

We are penperdicular to the road. Penperdicular. Penperdicular!

The man didn't seem to have any will left not to say it.

Penperdicular.

We stopped inside a residential building, front door ajar, and piled in on the first floor landing. Soviet-era signs still hаng on the walls:

Citizens, remember, 3 to 6 m^3 of water will leak, per day, out of a broken toilet tank. Perform timely repairs on your toilet tank.

Tenant comrades! Keep your section clean and tidy. (Here, someone had edited section to read pussy.)

This house has been released to the tenants for socialistic safekeeping.

He'd never seen such rubbish in his life. Not the signs. But to look at them!

Daddy, please calm down.

Things kept escaping, they were boiling over and out of him, and there wasn't much he could really do about it, it seemed. In the distance, the moan of train brakes scraped by at short intervals.

OK, dad, we're walking home.

It's far from here.

It's fine.

Then they crossed the tram tracks and were gone.

The guide was rather matter-of-fact about the man: It’s always a story when the locals show up. They always think they know better.

///

Vasyl Hlushko

Vasyl Hlushko grew up in a regular country family and is now retired. His mother had problems with her heart and when she fired up the stove she often lost consciousness. His father drank. In 1968 Vasyl was 15 and began working at the botanical garden. He cared for a sea of Dutch tulips and giant carpets of red and yellow roses. After this, he was a wagon-repair worker for 44 years. He was a carpenter, a master, a foreman. He fixed the breaks. He was, thank god, always good with his hands. Vasyl Ivanovich has been awarded two awards. The first award is the “Honorable Worker of Ukrainian Transport” award. The second award is for “Significant Personal Contribution to the Development of Railway Transport, Many Years of Hard Work, and High Professionalism”. Vasyl believes that flowers are able to transfer thoughts and feelings, especially when one cannot find these during an important moment. He keeps 500 tulips and 50 rose bushes. When the garden is asleep, Vasyl paints. For example, he has painted Albrecht Durer and Taras Shevchenko. Vasyl never wrote poetry, but then he had a heart attack and began writing some. He writes about the Ukrainian people, about their hangmen, about his hometown, and about his mother.

[source]

///

Elena Galas

Elena Galas is a blacksmith at DWRF, the Darnitsky Wagon-Repair Factory. She works in line with one hundred men. She is a punch-press operator. She is not a secretary, and she is not an accountant.

The men are taming metal and fire. Elena Galas is wearing an apron. She removes hot parts from a gas furnace and stamps them under a press. She is an udarnitsa — an enthusiastic superproductive laborer — of heavy male labor. Old complexes are replaced with new lofts, but the most beautiful roses are still on the Boulevard of Labor. Elena Nikolaevna started ten years ago. First she was in the foundry, and then she was in the forge. Her uncle and sister also work here.

The factory arranged Elena’s professional and personal life. Elena met Vitaly in the foundry, and now there is Zhenya, who will go to school next year. They live in a shared dormitory. Elena’s team is wonderful and friendly. The men do not offend Elena. They don’t complain about her work, even though she does it with her female hands and not with male force. At first it was hard for Elena to get used to the heat and the noise, but then she got “sucked into it”. She is not a grumpy woman, thank god. She does not quarrel. With special reverence, on March 8th, Elena’s colleagues congratulate her that she is a woman. This pleases her. But it is not only on this happy women’s holiday that the men do not forget she is a woman, they do not forget it throughout the year. They treat Elena like the most fragile part of the machine.

Elena Galas gets carried away when she speaks of devices; she speaks of things we cannot later recall. We look them up on Wikipedia and make believe these are the things she spoke of: mallets and flatters, fullers, swages, mandrels… The female blacksmith explains things to us we do not understand, so we go to her home in the hostel to photograph her in a familiar environment. We cannot believe Elena was wearing gray overalls before. What a hostess she is — everywhere we feel the female hand. Lena likes to plant flowers in flowerpots. Lena cooks different goodies in the kitchen.

It is nice when a person is happy with her family and work. But it is especially gratifying that in our time, even performing purely male work, a woman feels confident. So this is how our fragile women can be!

[source]

///

The river Darnitsya

The source of the river Darnitsya lies in the village of Knyazhichi (pop. 5207), between an 80,000-square-meter horse club, which is under full (indoor and outdoor!) video surveillance, and which, besides, has enough oats and hay for a 12-month period; a lake with a sign that reads Swimming is forbidden–the water does not correspond to sanitary norms; and a small grocery shop called Hope.

Darnitsya comes out of the earth, flows under a street named Laguna, and immediately becomes known as source and stream Plyakhoviy. If the villagers reproached the stream for thwarting their desires to dig root cellars, they probably did not show it. Its water, abundant and clear, was a gift.

Plyakhoviy, the bottle stream, the one to which to carry a vessel, flows to the west, towards Kyiv, in and out of Old Lake, in and out of New Lake, into cemented channels, where it becomes an artificial waterway, then into the pine forest near the DWRF district. Here, it dives head first into Bull Swamp, where there was something to do with bulls, a.k.a. Little Birch Lake, where the wagon-repair workers’ boys used to swim, a.k.a. Rainbow Lake, where in 2015 a certain Slavik, for 30 minutes, before dawn, struck the ice with a socket wrench, and the sound echoed through the forest. Slavik asks you to imagine this: a winter, a forest, a frozen lake, it's raining, it's pitch black. A large German shepherd arrives on the scene. She comes quietly and sits on the bank, watching, not barking, just watching. A wild duck quacks from the lake's far end. Slavik has made a meter-wide hole. Slavik goes in the hole.

What bliss, to dive fully, head and all, and, coming up again, to feel how an icy porridge slips down the head and the body, how a glorious burning heat pours into the body's nooks. Indescribable! Silence. Not a single living soul, not a single sound, just the rustle of the rain and the sound from the little chunks of ice rubbing against one another in the icy porridge of my ice hole! No desire to get dressed! The soul has unfolded and is striving somewhere, upwards, upwards… The drizzling rain became completely different – affectionate, dear, and kind... It seemed the life-giving energy overfilled each cell of my body!

When Plyakhoviy reemerges, it is once more the river Darnitsya. Seeping over thick mats of peat (which can burn for days in summer), it branches in two. The northern arm is a reclamation canal built by Stalin to drain swamps and fight malaria-carrying mosquitoes; it travels into “sleeper neighborhoods,” under their panel-block compounds and busy outdoor markets. The southern arm rushes (trickles on hot days) out of the forest to hug the Radical Chemical factory (“the Chernobyl of Kyiv”), hug the Kyiv Factory of Chemical Fibers, hug the Institute of Organic Chemistry, hug Cement Heaven, hug Steel Symphony, hug a very large refrigerated-truck transportation company, hug the #4 Darnitsya Heat and Power Plant (Kyiv’s oldest and most tired), and at this point, before it can find anything else to appreciate, it is caught in another reclamation canal.

The canal is mostly underground, except in some places, like under the bridge on Prague street, where the river Darnitsya comes up for air. Here, each day, the wagon-repair workers placed bets on what they’d find in the water. Back then, in the 1960s, red, purple, or orange froth were, reportedly, solid choices.

A churning yellow froth, says the son of a wagon-repair worker. And the forest turned yellow in a moment.

In 1509 you’d have bet on bream, idе, barbel, zander, pike, perch, and such-like others.

This past November, water like green syrup.

///

The contents of the river Darnitsya

Of course, we cannot know with certainty who put what in the water and when. Most of the surrounding factories wound down and rolled over in 1991 and the ensuing bandit years. When they still operated, the contents of the river were classified.

We do know that the workers of the Radical factory, for example, were paid three times as much as other factory workers and retired early. We know they produced chlorine, caustic soda, sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, potassium chlorate, DDT, and foam rubber.

There’s a floor which was specifically for producing mercury. I walked on the territory in my boots, it ate away at the leather… I worked in ’86 or ’87. And now it’s closed, it’s probably not working…. And they made DDT, on floor 22. It was very unpleasant to be on the territory.

To move around on the territory… new boots were gone immediately, at once, the leather, on the bottom. So saturated, the snow, was so saturated with filth…

Convicts, only convicts worked there…

We now know that, over the course of the 42 years of its operation, the factory released 700 tons of mercury into the environment, of which some portion was ingested by the river-bottom community of organisms in the river Darnitsya, accumulated, and converted into the even more toxic form of methylmercury. When, in 1996, the ecological inspection arrived to investigate the closed-down factory, they found 134 tons of mercury, 109 tons of sulfuric acid, 44 tons of mercury sludge, 62 tons of hydrochloric acid, 12 tons of ammonia, 486 tons of salt solvation, and close to 2500 tons of other waste, which was simply left to seep into the soil.

According to a member of the Green Circle citizen ecologists’ club, to the passerby, the curtain of secrecy and the sharp chemical smell emanating from the water of the river Darnitsya communicated a sense of danger that needed no devices and no analyses.

This danger inadvertently created unlikely protected zones, ad hoc nature reserves along the open portions of the river, such as the Grey Heron Swamp, which the club members discovered in 1989 as they traced it head to mouth. They were, the Green Circle member reports, astounded at the bounty and diversity of wild nature preserved in its untouchability.

///

Schooltime at DWRF

The pears and apples in the DWRF school orchard were off limits. Teachers knew that children carved the apples into hedgehogs with their fountain pens if given the chance.

One spring, the fourth-grade teacher took everyone outside to a small plot in the orchard. The plot was maintained by Aunt Faya, who lived in a small house in that orchard with a cat and a crow. The teacher said, you must investigate something here. She took a potato, cut it into quarters, put the quarters in the ground, and said, you'll be watching how this grows. The children had seen potatoes grow, and everybody knew nothing would come of this.

I walk through the pine forest towards the school. I pass some of the old green board fences on my way. Outside one of them, there is a bench, on which a man and a woman sit. They are with a caretaker. They tell me they are 92 and 97. They cannot hear well so it doesn’t matter what I tell them. They sing this song from 1859, separated into harmonies:

There is a tall mountain, and under it a grove —

a green grove, a thick grove, as if a paradise.

Under the grove winds a river; it shines like glass.

Through the valley green, it runs somewhere else.

At the bank’s edge, in quietude, boats are moored.

Three willows are bowed over, as if in sorrow,

that the red summer will end.

The cold will come, the leaves will fall,

and the water will carry them.

I am also sorrowful over the river…

it runs, it makes noise, and my poor heart swoons and hurts.

Oh river, blue! Just like your waves,

my joys and happy days, have run away.

Spring will return to you, beloved river.

But youth will never return. It won’t return!

There is a tall mountain, the grove buzzes.

Birds are singing loudly, and the river glistens.

How nice it is, how happy it is, to live in this wide world!

Why is it that my heart swoons and hurts!

It hurts with worry, that the spring will return.

But youth will… not return. It won’t return.

///

Weather in DWRF

It is necessary to note that none our observations are real — they are calculated based on archival weather. Moreover we do not guarantee that these specific plants grew and bloomed in Kyiv in these years. It is known that not all of the plants noted in the “Blooming Monitor” are native representatives of Kyivan flora; some were purposefully introduced or accidentally arrived very recently. The dates given are hypothetical — “when would this plant bloom if it lived in Kyiv during this year?” The ability of plants to predict the weather is not recognized — they may only know about the past, not about the future. Temperatures close to zero do not speed up nor delay the arrival of the event. It is thought that life processes simply freeze in the current position.

Such observations as “the hackberry blooms, expect a frost” and “leaves on an oak before an ash bode a dry year” are discarded. A few days after a thaw, there may (or may not) be a cold spell, and in this regard, there is nothing special about the hackberry.

[source]

a real russian new year

I'd woken up at three again

I'd sweated through my sheets (again)

I had even let myself sleep on my left side

Though that's where my face seems twice as large

The dentist said yes, I see what you've come here for,

I said, actually no, but interesting

Anyways I let myself sleep on my left side,

The comfort side,

Though that's the side where everything is wrong,

The foot is wider, the armpit smells worse, the pupil always dilates when it shouldn't, the knee is sore, the heart murmurs and skips a beat,

I had lied once in grade school and told Mr. C I had arrhythmia, and then ten years later it was true.

So I woke up and the sheets below were drenched, and the sheets above were drenched, and the wind outside rocked something new, or something old in a new way, screeching.

I thought, I must need to pee then.

Of course, I did not need to pee.

I did not need anything.

Or did I?

And was it the yearning and the emptiness that were already causing something to materialize?

He was sitting there in the corner when I came out to cross the living room.

In the dark of the couch.

Small and bearded, and making small grunts with his exhalations. Or was it his shoes that squeaked slightly, like he was an old plastic toy, chewed and dried out.

He was not a toy. He was, the only right way to describe him, gnome.

Glints in the dark, which I assume was him seeing me.

I thought, I will go to pee, and this will not be here when I cross again to return.

I did not need to pee, as I said.

Shame and revulsion passed through me so quickly I did not even notice them.

He was long-fingered, he wanted things, he insisted on his presence and rights to the couch. God, I hated him. I was afraid of him.

Furthermore, I knew I had to come out, naked, to sit with him.

//

it’s a real, russian new year, she explained

to her visiting boarding school friends.

we light candles like this all over the house

and drink Fernet Stock Citrus until we get acid reflux.

sometimes a body lies there on the floor

like a beached whale. we can step over it

or dress it up, like a doll, like a turkey.

but if you wake it, it will start wailing.

nobody was russian of course.

it didn’t matter, frankly. it didn’t matter to her at all.

they went out and took ecstasy.

and when they came home there was a hole in her nose

and a hole in her foot.

there was this nasty couch

not in that house, a different house.

they had been poorer, I guess,

it was black, with muted green and purple shapes,

a dusty galaxy;

and a black shelf the shape of a diamond.

with old pipes and embossed pens and other male things.

on sundays he was there in his sweatpants.

she couldn’t leave that couch, like a rift in space.

she made a fort behind it, so she could always be there,

keeping watch,

while they were watching TV.

she brought food, and a book, and colors.

I’m sure she’d have pissed in it and washed herself there if she could.

I remember a snowy winter when she’d gone out to play

on her own across the hills pulling the sled,

she went all the way to the lake

and forgot her self.

there were swans.

//

After the _________ I became demanding of myself but then also of everything around me. I wanted something, needed something, from the stream from the reeds from the way they were arranged in the middle of an iced reservoir.

I looked with a greediness and impatience at the willows and the piles of crushed stone. The ice forming in tyre prints I felt must hold ephemera or a very special small colony of organisms and only then will it all be worth it, would it all be justified. I longed for things to happen but was easily startled and frightened.

There are always things in the middle of these parks, the rails of the city’s electrical trains, a car atop a hill with its headlights on against the sun, the rowans of summer house ruins, dried pods curling and hanging from weeping branches. They all had to mean something and they usually did, but only later after I had already hurt myself with exasperation and impatience. Like a mother or a father, annoyed since before the child was even born, dragging them by the hand from something they do not like or do not want them to touch, or taking a pause after the child speaks to fully internalize their annoyance.

the Grey Heron Swamp

This is the sort of thing that should go in your Tinyletter, says P.

Alright.

Yesterday, in the midst of our crisis, I went on a search for some toxic water.

I feel like I’ve heard you say that before, says F.

But I'm basically always searching for toxic water.

The water, where it should have been, is mostly gone; half the swamp burned down, and the Roma camps; and the rainbow colors of the children's plastic alphabet letters are shriveled and now connote some other language, using other signs.

Don't go looking for augurs. The grey heron isn't here. The nest is tipped over and bends the willow to the ground. De Certeau says, Catastrophe is just another way for a field of discourse to uphold its privilege, it is just an inversion of progress. Better find the swarming, microbe-like activity of surreptitious creativities... So listen, I found papers burned around the edges into an almost perfect circle.

to take, for example, the eye of a cockroach,

which so ably captures an infrared ray,

and place it within a system of self-orientation

in a manmade Earth satellite, we must conduct

a special exploration of the living eye's reaction,

or, as they say, to calibrate the apparatus,

to determine its sensitivities,

its levels of its inner distortions.

When I hold the paper against the dark ground, it recedes into it, becoming an integral part, like a grotto or a treasure.

Above it, the plain where the train tracks meet. These tracks could protect these places, but they do not. On a slope, under some bushes, two men in baseball caps are digging holes. They are holding plastic bags. They are just hiding drugs for someone to find. This is called "bookmarks" or "treasures". Cache coordinates delivered to your Telegram on channels like @SandersSeller, @Aristoklad, @KFCmarket. Cyberpunk and secure. Don't forget your little garden shovel.

Someone's coming, he says.

The sun shines directly overhead; so are they; I shade my eyes to see them.

They seem worried now, but I wonder how long it'll be until they realize that I am a woman.

Before setting out, I had prepared a few phrases:

[Holds up card.] Press. Noha Magazine. I am searching for the grey heron. Have you seen it? No? Alright. Do you come here often? Mhm. Mhm. Thank you for your time.

This doesn't feel appropriate to the occasion. Turning around feels like an overreaction. I walk on. A butterfly, brick red and brown, lands on a dry stalk in front of me. It's time to take some pictures of this butterfly. I am not very interested in it, and it's hard to photograph on my shitty phone, but I make the effort. It would make my intentions clearer.

What is she snooping around here for?

Fuck if I know, shoot the bitch.

[Unintelligible.]

Shoot her.

I turn around. Calmly, but does it matter? Yes, I turn around calmly, and slowly walk back. Rocks fall softly behind me.

I could give two shits about this homework right?...

I just want to play Dota, you know?...

Some boys are playing by the railway bridge. By playing I mean they are taking Instagram pictures and are dressed like goths.

Greetings.

Greetings.

How do you do?

Excellently, how do you do?

We too are excellent. We wish you a Happy New Year!

And a Merry Christmas!

I walk for a long time along the train tracks, then climb out of that patch of earth between the rails and reemerge near a "civilized" park. It's really a bike lane and a two-baby-carriage-wide walk space around a lake, nicely paved, with tiny evergreen saplings planted around the perimeter, which look vulnerable and out of their element. This is something I'd laugh about, something the KZB municipal landscaping organization lives by.

what are

changes

grown

and

park squares

after such a

lawn!

But I'd be lying if I said I did not then and there enjoy consuming my packed banana, in the shade of a cultivated tree, on this well-kept lawn, amidst the Rottweilers and the evening joggers.

On my Uber ride home, the ads show the Kyiv mayor, the former boxer Klichko, rolling up his sleeves. They read, Stop snooping around!

(I will not, however.)

A SPONDYL CLAY BRICK FOR OLEKSANDER OSIPOV

1/6

If you ever go looking for the Kurenivka clay quarry lake, taking the road up from Syrets metro station, through the rising coolness of Syrets grove, and along the Syrets stream -- cement-encased, but pillowed in on each side by the silvering rustle of Russian olive (here, we call that tree a dumbass) -- you might chance upon several packs of street dogs, one of which will introduce you to Slava, who lives in a train car.

These days, the old brick factory is full of mattresses, pants, Ceresit CT 83 strong fix adhesive mortar for thermal insulation, rolls of high-quality galvanized steel mesh, and other things Slava keeps an eye on. Tusya is a good girl, and no longer bares her teeth.

Tucked in among the warehouses and rusted excavators, there is a 15-foot blue clay shelf. Thick patches of tufted vetch, colt’s foot, and mugwort are erupting out of its crusty head. Below, on the cracked plateau, a field of cream-tipped melilot buzzes and sways. Have you ever heard a field of sweet clover whisper conspiratorially? It does that, when the wind is blowing in the storm clouds.

2/6

Another time, Slava tells me that the blue clay was dumped here by KyivMetroBud -- the municipal subway construction company. The quarry is filled with water, the brick factory is stuffed with mattresses, but the clay keeps coming, as though summoned by something within the earth.

Mr. I. V. Ogorodnik (translation: “Gardener”) of the PORCEKS VRBT* research center for ceramic technologies offers the following assessment of thе clay: “Of the raw clay materials in the Kyiv region, a significant proportion is occupied by blue-gray marl clays -- located in the lower Tertiary deposits of the Kiev tier; they are known as “spondyl clays”, since they contain the spines/thorns of Spondylus buchii molluscs."

Mr. I. V. Gardener’s company is concerned with a clay’s commercial usability in construction. Mr. Gardener wishes to minimize transportation costs by finding usable clay within Kyiv's city limits (a quarry for every neighborhood!). But, lamentably, building with spondyl clays is economically nonviable. Like all other clays in the region, they contain too many salts.

3/6

There was too much sea here. With nipa palm along the coast, swaying warm, wet, subtropical. The Earth's crust rose, fell, and rose again, and the sea dried up, baring the bodies of acidified spondylus molluscs, that had cooked (on kimberlites erupting diamonds? a 50-square-mile volcano? methane released from crystal cages of ice?), then cooled, now died.

Thousands of years later, Fonga Sigde, shell procurer, will scatter powdered spondylus in a carpet before the Chimu king’s feet, while high in the Andean cloud forests, they'll be sacrificed, for food, for vital water, for rain.

It started to rain. Rivulets ravined and made the Dnipro. In Finland, azolla ferns froze and sank, and from some northern cirque, a wall of ice unfurled, slid and crushed its way down, plucking rocks out of their pockets -- granite, gneiss, diabase, mica, chlorite, sandstone, silt, dolomite -- rubbed them round, and strew them across the fields and hills of Kyiv.

We’ll find this a pain in the ass when those fields need to be ploughed. There’s a saying -- нашла коса на камень, the scythe has landed on the rock. P. explains: “it means to meet your match -- when two coequal people, or situations, find one another”.

Sixty feet under, the unviable bodies of spondylus molluscs rest in a thick layer of blue-gray cream clay.

4/6

In 1961, the clay pulp refuse from the Kurenivka brickworks needs to spread out -- so it slides and crushes its way down the ravine, killing over 1500 or 3000 local residents. We cannot know for sure, as the government found talking about tragedy difficult. Afterwards, people would say that this happened because the earth sought its revenge over the Germans’ and Ukrainians’ massacre of 34,000 Jews in that ravine in 1941. I don’t see why this should be so. If the clay was angry, it surely had reasons of its own. But its spreading out seems contented, peaceful, not vengeful.

Across the street from this ravine, at the Kyiv city archives, I’m warming my hands on wet, thermos-steam warmth, and looking at a 400-page chronicle of one man’s frustration.

5/6

When in 1890 Oleksandr Osipov decided to build a Kyiv gardening school, he never imagined it would be so difficult. After all, it was he, Oleksandr, who had spurred the creation of the government’s Garden Committee in 1886, founded the Kyiv Division of the Russian Imperial Horticultural Society in 1887, lined the city streets with trees in 1888, and then, in a glorious apotheosis, lit up St. Vladimir’s blazing cross using electricity sourced from a local railway station.

The school (officially, the School of Orchardry and Gardening With Instruction in Silkworm Husbandry, Beekeeping, Carpentry, and Basket Weaving), moreover, made sense.

For starters, there wasn’t one. Good gardeners were in short supply. There was money left by someone dead, and 15 desyatinas of promised public land in the Kurenivka neighborhood, which was practically teeming with people who apparently gardened out of an “heirloom compulsion”. The Krister Brothers -- Kyiv’s green barons -- pledged saplings, bushes, and their full support. The Society of Agriculture received a pomological collection representative of the entire Kyiv region, which it deposited into its grand inventory of apiaries, secateurs, sericulture implements, and other things left over from the Agricultural Exposition it didn’t know what to do with. And there was a recent cohort of orphans who would enjoy, everyone was sure, turning mulch and cross-breeding Asian and Ukrainian pears.

During a golden jubilee party at a Kurenivka parochial school, count Ignatyev raised a toast to the gardening school’s future success. The Kurenivka locals who were present raised it with him, and those who had stayed at home felt a warm surge in their veins, as their ancestral horticultural predispositions were recognized, underwritten, and directed into higher education.

Syllabi and floorplans were lovingly, meticulously sketched out; hundreds of pages of letters in longhand; articles in the local papers; reports on council meetings; budget estimates, many, dreaded budget estimates. The project’s materials made it into larger bureaucratic arteries, were scrutinized, rejected. Then resent, reexamined, dissected, contingently allowed into a new chamber. Forgotten, remembered. Written about. Haven’t we sent that document already?

Halfway through, the gardening school chronicles pronounce Oleksandr Osipov dead. And, for the first time, we lock eyes.

A two-hundred-page denouement. The Garden Committee fervidly pledges to continue his legacy -- to make real his last great work, so near to completion that it’s almost palpable. A few more budget estimates are made by an agronomist, one by an economist. Some tired voice -- its interlocutor now dead (‘for god’s sake, when will I retire?’) -- repeats that “the project is impractical”. Some tumbleweeds blow across the 15 desyatinas of land in Kurenivka.

1917 arrives. All previous things lose their names.

6/6

The bacterium Pseudomonas syringae can be found floating on algae latched between ice crystals, riding your local pollen causeways, or traveling by bee. But one of its favorite places to be is with the pea family, where it will seek out sweet clovers and vetches over others. If it finds an entire monoculture field of delicious, edible peas, it goes nuts, producing “sunken, dry, necrotic, light-brown lesions” and a terrible reputation with agrobusiness.

On regular days it makes rain.

Have you ever heard a field of sweet clover whisper conspiratorially? Nestled in the folds of their leaves, colonies of P. syringae grow and wait for a proper gust of wind. When it comes, they sweep into the sky, find water molecules, and make them heavy enough to drop.

It takes four to six years for sweet clovers to arrive on clay quarries and demolition sites. It might be another six before this place sees an ash or an elder. Thin, dry, poor, needy earths only make room for the most intrepid. By the time the clovers and vetches are there, it’s starting to eat well, and when the storm clouds roll in, the pores of the ground open up with yearning.

*

PORCEKS VRBT

In the "About Us" section, the company explains:

PORCEKS stands for:

PORCEliana (Porcelain)

Keramika (Ceramics)

Steklo (Glass, also: "seeped away")

Vmeste (Together)

Rabotat (We work)

Budusheye (The future)

Tvorit' (We create)

Updates from the Vidradniy Neighborhood, Kyiv

[Update 1:

The house across the street has trees and flowers. We have a parking lot.

Yes, these cars are working horses, but when they’re gone, that yard is like a proving ground for tanks. Moving the cars will be a problem. After all, we have the most criminal neighborhood in Kyiv, we’re even ahead of Troyeshchina. They’re bombing apartments and cars. You’re mugged in the streets.

A long time ago, everything was good. Lawns, hedges, and rowan trees. And gooseberries under the balcony. Currants, tulips, sand, and benches. And children playing.

Now, the children play at the office supply store, Papyrus. And flowers only grow under the balconies of the hotel.]

///

The grass-leaved rush is grass-leaved, but it isn’t grass. Colonial secretary of Tasmania James Ebenezer Bicheno called the entire genus (Juncus) “obscure and uninviting”. But that man held conservative views at a time of great social change and, it was said, could fit three full bags of wheat in his pants.

It lives in wet meadows, marshes, seepage areas, and along ponds. I find it in a big, dry basin.

There was water here once.

When we weren’t born yet?

No, we were already born then.

Yes, and then it seeped away, and what was left was just a hole.

Yes, and people started throwing garbage in it.

But then they cleaned it up.

///

[Update 2:

Everybody knows and understands the state of the elevator. But Svetlana is surprised that there is no contact information, or call buttons inside. Sometimes, she wonders what sticky substance was used to affix the mirror… and who broke it? and who spits on it?]

[Update 3:

On the 25th of February at Orlyatko park, people enjoyed pancakes with tea, won prizes, played children’s games, and listened to a military orchestra. On the 8th of March, Vadim Sergeevich congratulated all the women, wishing they’ll smile, be loved, and always stay beautiful. Tatyana Vereninova thanked him.]

///

Здесь был раньше… (This used to be a…)

Фонтан! (Fountain!)

Фонтан, да. (A fountain, yes.)

А его скоро починят? (Will they fix it soon?)

Даже не знаю... Стекло, стекло здесь. (I don’t even know. It’s seeped away / also: there’s glass.)

I hold up some toadflax against the dried-up fountain. We don’t really call it that. Sometimes we call it wild flax. Or doggies.

A year passes.

Now, the rush. And horehound. And spotted lady’s thumb. Indicating gone wetlands. Horehound makes black dye. Lady’s thumb makes yellow. Behind them, fragments of granite slab and ceramic tile waver in the heat they’ve trapped that July day. I’ve never seen it, but spring could see this place filled with water.

///